Climate Action at the Coal Face:

'In the heart of the beast!'

Michael Apathy (pronounced Apayti – there’s nothing apathetic about Michael!) is a psychotherapist in Ōtautahi Christchurch. So how did he find himself chained to a conveyor belt at a coal mine in Southland?!

Silvia Purdie interviewed Michael about the events of Monday 2 May 2022 at the Takitimu Coal Mine in Southland and about his motivation and passion for direct action on climate change.

Silvia Purdie interviewed Michael about the events of Monday 2 May 2022 at the Takitimu Coal Mine in Southland and about his motivation and passion for direct action on climate change.

So how did it go?

A large team action is a whirlwind! At some point I ask myself, "Why on earth am I doing this?!" But our Takitimu Mine occupation went really really well.

What stands out for you?

It was a great moment at 5.00am on Monday morning. We had succeeding in getting in and we were all in place within the coal mine; the towers were set up at the entrance, our people were locked on, the climbers were in place, we had a boat on the lake. “We made it! We have taken possession of this space.” Suddenly I felt a huge buzz and delight, that lasted through the whole day, and since.

It was a lot of work to get there, plenty of tasks and frustrations, worries and anxieties. We had a detailed plan but it was pretty frantic getting set up. We came in very quiet and discreet, expecting there to be a nightwatch guard, but there was no one there. There didn't seem to be any cameras or alarms, so it was actually very easy. So there we were, in the dark at 5.00am. My team were hanging above me up on the conveyor belt, and together we had a moment of celebration.

Where were you?

I was at the base of the coal conveyor machine, on a walkway. My two buddies had climbed up with ropes and set up our banners: big native bird flags and banners saying “Keep nature, quit coal." So they were strapped in their hammock and I was on the ground underneath so that workers or police couldn't immediately climb up and remove the flags and banners. When the police came along I put both of my arms into a 90 degree pipe lock and I was not movable. That was my gig.

I was also there to look after the climbers because they were new to activism. A wonderful thing about this action was that we had some new people come along who are very capable. It's a big thing, emotionally and psychologically, for someone to decide, "Right! I’m going to put myself in this situation, with a bunch of people I don't know, and risk arrest or abuse." We didn't know how rough our reception from others would be, so it's a big ask first time around.

Did you hear about why they came?

When I am working with people I love to hear about their motivation for being there. But in gearing up for the Takitimu action it was all such a rush. When I talked with the new people I was walking them through the arrest process: what do police say to you? What sorts of questions do they ask? What do you have to answer? What happens if they take you in a paddy wagon to a cell? What are the possible consequences? The 'why' is super important, but that day it was all focused on the 'how' – how we're going to pull this off!

What other roles did you carry with the group?

Responding to the climate emergency is emotionally demanding. Part of how I see my role is to attend to emotions and how we are communicating, for the wellbeing of the group. To pull off a major action is stressful at times. We have different perspectives and misunderstandings and sometimes get snappy. It is vital to keep talking. We are committed to this for the long haul and we are committed to each other. This takes emotional labour.

The culture of our group process is important, to be warm and encouraging and honest with each other. It is also important to take time to pause. At one point in our planning we stopped and I guided a short meditation: "OK, we're going to take 10 minutes." Everyone closed their eyes and was guided to connect with: “What is the thing that is motivating you?” Whether that's love of non-human life; whether it's passion for justice for people who are less privileged who are already having their lives upended by the climate crisis; whether that is concern for future generations. We come from all sorts of different angles and we are motivated by many things. I guided a process to get in touch with that and embody that.

And then to open our eyes, look around the room and see that you are not alone. All these other people are motivated by these things as well. It is a rare and wonderful thing to be with a bunch of other people with this as our sole focus. Together we are taking action for maximum impact. It gives strength to pause and feel that. Knowing there are others there with you is very supportive; you have got my back and I've got yours.

What motivates you?

For me, when I connect with my motivation, there's a lot! I definitely think about young people who are going to have life harder than me and who won’t have the privileges that I've had. There's a real protective passion in me – I don't have kids of my own but I still have that parental nurturing feeling. There's the whole piece about injustice. Climate crisis is an extension of colonisation and patriarchy and these awful exploitative mechanisms that are so unnecessary and destructive. There is a smoldering layer of anger in me that wants to dismantle this. We have built a system that is destroying our ecosystem. We have built it and I want to take it apart again! I feel very aware of all the non-human life we are exterminating through emissions, including the emissions from this mine through burning coal. We are exterminating species that we won’t even get a chance to discover. That is horrific. We do not have the right. I could go on, there are many.

What was it like being right there inside the coal system?

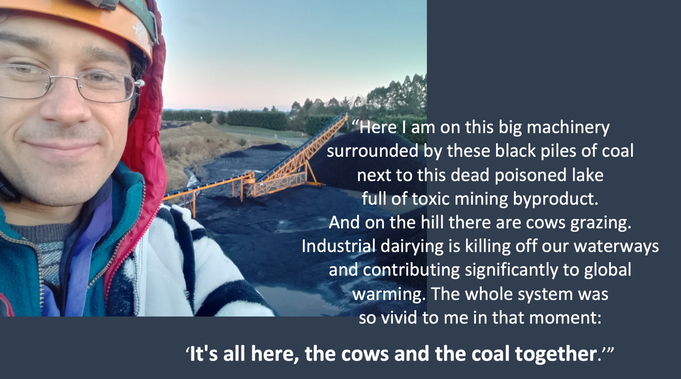

As the sun rose, the first thing that came to mind for me was how great it was to actually be there and to see it. There I was, inside the mine, surrounded by all the giant piles of coal, literally inside the machinery that extracts it. Coal is such an abstract thing to so many of us. I talk to people and they are surprised: "We still mine coal in New Zealand?!" It is out of sight, out of mind. Being there made the climate crisis very real, rather than just numbers in a news article or spreadsheet.

I laughed; it was so stark. Here I am on this big piece of machinery surrounded by these black piles of coal next to this totally dead poisoned lake full of the toxic byproduct of the mining. And on the silhouette of the hill there are cows grazing. We have learned a lot about the whole industrial dairying system that is killing off our waterways and contributing significantly to global warming. This is a key reason why New Zealand is actually really terrible in terms of climate change. This coal goes to Fonterra to be burned to dry milk powder to be shipped overseas. The whole system was so vivid to me in that moment: "It's all here, the cows and the coal together.”

It was warm and still. We were so lucky to have a gorgeous day. The weeks before had been frantic with so many different things to do to get to that point. But when we were there and actually occupying, it became just holding the space. I found it very meditative; sit there and be. Even though I'd had no sleep I had this peaceful, energetic, joyful feeling throughout the day. It became a meditation on being in the heart of the beast.

So then what happened?

Gradually workers and police showed up. While it was still dark the first worker arrived, with no idea we were there. At the gate we made these giant moving puppets – eerie, almost apocalyptic. If you can imagine turning up to work on Monday morning, at about six o'clock, you're the first person in the mine, driving up towards the gate and you just see this giant spooky figure looming in the night. The guy drove up, saw it, turned around straight away and drove off! It must have been the most surreal experience for him.

We were worried that the initial reaction by workers or police might potentially be violent towards us, but it was actually a chilled out start, which was good. As the day began, more workers arrived. Police showed up, at first the local police and then more police from around Southland and Otago. For much of the day I was surrounded by several police officers, with a police negotiator talking to me and trying to pressure me into leaving.

Was there a bad moment?

The riskiest moment of the action was when one of the locals came up and verbally unleashed at the people at the tower. His yelling wasn't dangerous in itself, but then he started shaking the tower that two of the activists were on, four meters up! Eventually he settled down, and thankfully it didn't get too curly. I was glad that the mine manager and the staff were professional and let the police handle things. We'd much rather deal with the police in those situations.

Did you achieve what you set out to?

We got heaps of attention from the media which was excellent. It was a chance to tell our story and to put a real focus on the issues. It culminated in Parliament with media questions that evening during the Cabinet briefing. One of the journalists specifically named our action earlier that day and asked about the transition away from fossil fuels: ‘the government has said some good things about transitioning, but hey what's happening with this coal mine still expanding?’ The prime minister said her piece and then another journalist asked a further challenging follow up question. It was great to have that highlighted. It helped us feel that we are shaping public attention and understanding.

The backdrop is that we have an incredibly distorted story in Aotearoa. The majority of the public thinks that climate change is really important and that stuff needs to be done about it. But the majority of the public also thinks that we are doing pretty well. And we're not. We are up there amongst the worst countries. We fall well short.

How did it end?

We had supplies to last a couple of days, but towards the end of the afternoon we decided to leave. It was a consensus group decision. Enough people were feeling concerned about staying overnight, and it was important to us to be totally cohesive as a group. We felt that we had done a good job, and it was the right thing to leave with everyone in a good shape. The decision was made fairly easily.

Thankfully there was good cell coverage in the mine, so we could stay in touch with each other on our phones. That made things a lot easier than a few years ago when we occupied Coalgate coal mine where there was no cell reception; that was a lot harder.

At that point there were seven police officers around me and the police negotiator was begging me to unlock. So I said, "OK. So if I unlock, you will not arrest me?" And she said, “Yep”, so I said, " Alright, let's do this." And we walked out. It ended with no one being arrested so that was nice. Being arrested would have been fine, but not being arrested is easier on the activists of course.

What was it like coming out?

We all unlocked and came down from our climbing positions, and as we walked to the gate we were greeted by a big crescendo of drumming and singing, a celebration of what we had done. It was so beautiful and emotionally connecting. That moment from this action, and similar moments at other actions I've done, are lovely memories to hold on to. It made you feel you are part of this thing which is a work of art as well as a political action.

A work of art!? Why do you include celebration into protest?

At the entrance gate people were deliberately fun and light-hearted, creating a bit of a festival vibe. We are taking very serious action about the existential threat of climate change. We are doing an action that we know is disruptive and is going to piss some people off. We need to be really careful around safety and very clear about what we are trying to achieve. So direct action like this is an intense and serious thing. But admidst that there was music and dancing. We hung beautiful colourful flags. People wore silly cow onesies. It is important to us that direct action becomes light and playful and a celebration all at the same time. Even the police were feeling it. At one point they asked us to put on some Pink Floyd. So we played that on the speaker and you could tell they were enjoying it. Some of them would have joined in the boogy but they weren't allowed.

The tone is different for different actions. Some actions have a grave tone to them. For instance, I remember we did an action during the massive Australian bushfires massive when our skies were dark and clouded over. There was an apocalyptic feel. So that action was about coming together and bearing witness and it was sombre. And on the other end of the spectrum we were dancing in cow onesies to 'Staying alive' in front of the Wellington train station. We are still had a powerful message but we made it light and fun. And suddenly school kids on their way to school were joining in and dancing.

Our point was that we don't have to just focus on the fact that this is terrifying and desperate. Making changes and engaging politically should be fun at times and nourishing. That is lacking from our system. No wonder we don't get public participation when we have these terrible submission processes where you can come and you can speak to a bunch of politicians who aren't looking you in the eye or giving you any human response. That is not a set up designed for human participation. We need connection and play and responsiveness.

How was the group afterwards?

After our actions we always debrief together. People express joy or celebration: "We did this big thing, we were successful!" Some people spoke about how good it feels to actually take action. Many people experience climate anxiety. It builds up inside people and urges them: "Shit, we have got to do something!" After an action there is a real sense of relief from that anxiety: "We have done this big thing!" Even though we know it is still just a drop in the bucket. The sense of empowerment is important for us.

How is protest action empowering?

Our process is very empowering; come because you are a human being. You don't have to have technical expertise or a doctorate. Just be human. The power is in not doing what you are told to do. Be places you are not supposed to be. Do not consent to business as normal. You can have a lot of power just by not consenting to ‘normal’. If more of us could know that and do that, it would change everything.

A large team action is a whirlwind! At some point I ask myself, "Why on earth am I doing this?!" But our Takitimu Mine occupation went really really well.

What stands out for you?

It was a great moment at 5.00am on Monday morning. We had succeeding in getting in and we were all in place within the coal mine; the towers were set up at the entrance, our people were locked on, the climbers were in place, we had a boat on the lake. “We made it! We have taken possession of this space.” Suddenly I felt a huge buzz and delight, that lasted through the whole day, and since.

It was a lot of work to get there, plenty of tasks and frustrations, worries and anxieties. We had a detailed plan but it was pretty frantic getting set up. We came in very quiet and discreet, expecting there to be a nightwatch guard, but there was no one there. There didn't seem to be any cameras or alarms, so it was actually very easy. So there we were, in the dark at 5.00am. My team were hanging above me up on the conveyor belt, and together we had a moment of celebration.

Where were you?

I was at the base of the coal conveyor machine, on a walkway. My two buddies had climbed up with ropes and set up our banners: big native bird flags and banners saying “Keep nature, quit coal." So they were strapped in their hammock and I was on the ground underneath so that workers or police couldn't immediately climb up and remove the flags and banners. When the police came along I put both of my arms into a 90 degree pipe lock and I was not movable. That was my gig.

I was also there to look after the climbers because they were new to activism. A wonderful thing about this action was that we had some new people come along who are very capable. It's a big thing, emotionally and psychologically, for someone to decide, "Right! I’m going to put myself in this situation, with a bunch of people I don't know, and risk arrest or abuse." We didn't know how rough our reception from others would be, so it's a big ask first time around.

Did you hear about why they came?

When I am working with people I love to hear about their motivation for being there. But in gearing up for the Takitimu action it was all such a rush. When I talked with the new people I was walking them through the arrest process: what do police say to you? What sorts of questions do they ask? What do you have to answer? What happens if they take you in a paddy wagon to a cell? What are the possible consequences? The 'why' is super important, but that day it was all focused on the 'how' – how we're going to pull this off!

What other roles did you carry with the group?

Responding to the climate emergency is emotionally demanding. Part of how I see my role is to attend to emotions and how we are communicating, for the wellbeing of the group. To pull off a major action is stressful at times. We have different perspectives and misunderstandings and sometimes get snappy. It is vital to keep talking. We are committed to this for the long haul and we are committed to each other. This takes emotional labour.

The culture of our group process is important, to be warm and encouraging and honest with each other. It is also important to take time to pause. At one point in our planning we stopped and I guided a short meditation: "OK, we're going to take 10 minutes." Everyone closed their eyes and was guided to connect with: “What is the thing that is motivating you?” Whether that's love of non-human life; whether it's passion for justice for people who are less privileged who are already having their lives upended by the climate crisis; whether that is concern for future generations. We come from all sorts of different angles and we are motivated by many things. I guided a process to get in touch with that and embody that.

And then to open our eyes, look around the room and see that you are not alone. All these other people are motivated by these things as well. It is a rare and wonderful thing to be with a bunch of other people with this as our sole focus. Together we are taking action for maximum impact. It gives strength to pause and feel that. Knowing there are others there with you is very supportive; you have got my back and I've got yours.

What motivates you?

For me, when I connect with my motivation, there's a lot! I definitely think about young people who are going to have life harder than me and who won’t have the privileges that I've had. There's a real protective passion in me – I don't have kids of my own but I still have that parental nurturing feeling. There's the whole piece about injustice. Climate crisis is an extension of colonisation and patriarchy and these awful exploitative mechanisms that are so unnecessary and destructive. There is a smoldering layer of anger in me that wants to dismantle this. We have built a system that is destroying our ecosystem. We have built it and I want to take it apart again! I feel very aware of all the non-human life we are exterminating through emissions, including the emissions from this mine through burning coal. We are exterminating species that we won’t even get a chance to discover. That is horrific. We do not have the right. I could go on, there are many.

What was it like being right there inside the coal system?

As the sun rose, the first thing that came to mind for me was how great it was to actually be there and to see it. There I was, inside the mine, surrounded by all the giant piles of coal, literally inside the machinery that extracts it. Coal is such an abstract thing to so many of us. I talk to people and they are surprised: "We still mine coal in New Zealand?!" It is out of sight, out of mind. Being there made the climate crisis very real, rather than just numbers in a news article or spreadsheet.

I laughed; it was so stark. Here I am on this big piece of machinery surrounded by these black piles of coal next to this totally dead poisoned lake full of the toxic byproduct of the mining. And on the silhouette of the hill there are cows grazing. We have learned a lot about the whole industrial dairying system that is killing off our waterways and contributing significantly to global warming. This is a key reason why New Zealand is actually really terrible in terms of climate change. This coal goes to Fonterra to be burned to dry milk powder to be shipped overseas. The whole system was so vivid to me in that moment: "It's all here, the cows and the coal together.”

It was warm and still. We were so lucky to have a gorgeous day. The weeks before had been frantic with so many different things to do to get to that point. But when we were there and actually occupying, it became just holding the space. I found it very meditative; sit there and be. Even though I'd had no sleep I had this peaceful, energetic, joyful feeling throughout the day. It became a meditation on being in the heart of the beast.

So then what happened?

Gradually workers and police showed up. While it was still dark the first worker arrived, with no idea we were there. At the gate we made these giant moving puppets – eerie, almost apocalyptic. If you can imagine turning up to work on Monday morning, at about six o'clock, you're the first person in the mine, driving up towards the gate and you just see this giant spooky figure looming in the night. The guy drove up, saw it, turned around straight away and drove off! It must have been the most surreal experience for him.

We were worried that the initial reaction by workers or police might potentially be violent towards us, but it was actually a chilled out start, which was good. As the day began, more workers arrived. Police showed up, at first the local police and then more police from around Southland and Otago. For much of the day I was surrounded by several police officers, with a police negotiator talking to me and trying to pressure me into leaving.

Was there a bad moment?

The riskiest moment of the action was when one of the locals came up and verbally unleashed at the people at the tower. His yelling wasn't dangerous in itself, but then he started shaking the tower that two of the activists were on, four meters up! Eventually he settled down, and thankfully it didn't get too curly. I was glad that the mine manager and the staff were professional and let the police handle things. We'd much rather deal with the police in those situations.

Did you achieve what you set out to?

We got heaps of attention from the media which was excellent. It was a chance to tell our story and to put a real focus on the issues. It culminated in Parliament with media questions that evening during the Cabinet briefing. One of the journalists specifically named our action earlier that day and asked about the transition away from fossil fuels: ‘the government has said some good things about transitioning, but hey what's happening with this coal mine still expanding?’ The prime minister said her piece and then another journalist asked a further challenging follow up question. It was great to have that highlighted. It helped us feel that we are shaping public attention and understanding.

The backdrop is that we have an incredibly distorted story in Aotearoa. The majority of the public thinks that climate change is really important and that stuff needs to be done about it. But the majority of the public also thinks that we are doing pretty well. And we're not. We are up there amongst the worst countries. We fall well short.

How did it end?

We had supplies to last a couple of days, but towards the end of the afternoon we decided to leave. It was a consensus group decision. Enough people were feeling concerned about staying overnight, and it was important to us to be totally cohesive as a group. We felt that we had done a good job, and it was the right thing to leave with everyone in a good shape. The decision was made fairly easily.

Thankfully there was good cell coverage in the mine, so we could stay in touch with each other on our phones. That made things a lot easier than a few years ago when we occupied Coalgate coal mine where there was no cell reception; that was a lot harder.

At that point there were seven police officers around me and the police negotiator was begging me to unlock. So I said, "OK. So if I unlock, you will not arrest me?" And she said, “Yep”, so I said, " Alright, let's do this." And we walked out. It ended with no one being arrested so that was nice. Being arrested would have been fine, but not being arrested is easier on the activists of course.

What was it like coming out?

We all unlocked and came down from our climbing positions, and as we walked to the gate we were greeted by a big crescendo of drumming and singing, a celebration of what we had done. It was so beautiful and emotionally connecting. That moment from this action, and similar moments at other actions I've done, are lovely memories to hold on to. It made you feel you are part of this thing which is a work of art as well as a political action.

A work of art!? Why do you include celebration into protest?

At the entrance gate people were deliberately fun and light-hearted, creating a bit of a festival vibe. We are taking very serious action about the existential threat of climate change. We are doing an action that we know is disruptive and is going to piss some people off. We need to be really careful around safety and very clear about what we are trying to achieve. So direct action like this is an intense and serious thing. But admidst that there was music and dancing. We hung beautiful colourful flags. People wore silly cow onesies. It is important to us that direct action becomes light and playful and a celebration all at the same time. Even the police were feeling it. At one point they asked us to put on some Pink Floyd. So we played that on the speaker and you could tell they were enjoying it. Some of them would have joined in the boogy but they weren't allowed.

The tone is different for different actions. Some actions have a grave tone to them. For instance, I remember we did an action during the massive Australian bushfires massive when our skies were dark and clouded over. There was an apocalyptic feel. So that action was about coming together and bearing witness and it was sombre. And on the other end of the spectrum we were dancing in cow onesies to 'Staying alive' in front of the Wellington train station. We are still had a powerful message but we made it light and fun. And suddenly school kids on their way to school were joining in and dancing.

Our point was that we don't have to just focus on the fact that this is terrifying and desperate. Making changes and engaging politically should be fun at times and nourishing. That is lacking from our system. No wonder we don't get public participation when we have these terrible submission processes where you can come and you can speak to a bunch of politicians who aren't looking you in the eye or giving you any human response. That is not a set up designed for human participation. We need connection and play and responsiveness.

How was the group afterwards?

After our actions we always debrief together. People express joy or celebration: "We did this big thing, we were successful!" Some people spoke about how good it feels to actually take action. Many people experience climate anxiety. It builds up inside people and urges them: "Shit, we have got to do something!" After an action there is a real sense of relief from that anxiety: "We have done this big thing!" Even though we know it is still just a drop in the bucket. The sense of empowerment is important for us.

How is protest action empowering?

Our process is very empowering; come because you are a human being. You don't have to have technical expertise or a doctorate. Just be human. The power is in not doing what you are told to do. Be places you are not supposed to be. Do not consent to business as normal. You can have a lot of power just by not consenting to ‘normal’. If more of us could know that and do that, it would change everything.