Pumpkins on the road

|

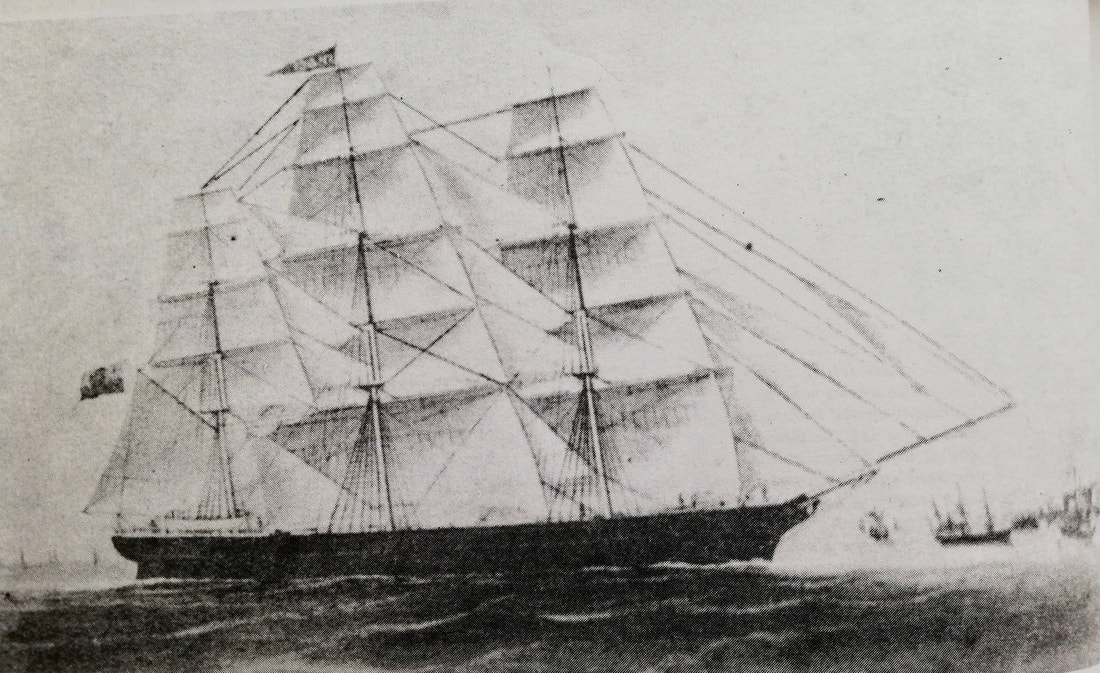

The England, the second ship to bring Scandinavian immigrants to NZ, 1871.

|

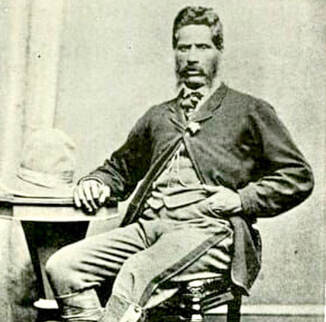

Chief Peeti Te Awe Awe

|

My father’s grandfather was Las Lassen. In 1870, aged only 17, he set off alone for New Zealand from his home on the Danish island of Als. He got himself to Gravesend in England then boarded a ship called the ‘England’ together with other Scandinavian immigrants, all of whom had pre-purchased land north of Palmerston North. After 104 days at sea they landed in Wellington on 19 March 1871, then set off to the Manawatu. A steamer carried them up the coast to Foxton, where they loaded their possessions onto carts and set off on foot. Unfortunately for them it was a particularly wet autumn, so it was mud all the way, bogging the cart wheels and making for slow progress. By the third day (10 April) they had reached the Maori (Rangitane) village of Ngawhakarau on the banks of the Manawatu River.

"There they found that the villagers had prepared a welcome gift for them. A number of kete [flax baskets] of potatoes and several tons of pumpkins had been piled at the roadside for them to collect. When the Scandinavian party drew alongside, the chief of the village, Te Peeti Te Awe Awe, welcomed them, saying that the Maori were glad they had come to make roads and to live in this country. He was aware that they had no potatoes and asked that they accept this gift of food and seed, adding that at some time in the future some poor Maori may have need of a similar gift from them." (Val A. Burr, Mosquitoes and Sawdust: A History of Scandinavians in early Palmerston North and Surrounding Districts, Palmerston North, NZ: Scandinavian Club of Manawatu, 1995, page 26)

This generous act of friendship made a big impression on Lars and his companions, and they were most grateful. It did, however, cause a practical dilemma – how to transport the potatoes and pumpkins. The decision was made to unload one of the carts, leave behind the baggage it carried to collect later, and load up the vegetables instead. By night fall they made it into Palmerston North, and the following day Lars set foot on his new land. Sadly for the owners of the items left behind at Ngawhakarau, the weather went from bad to worse, the river rose and their possessions were swept away!

This story, a treasured part of my family history, has particular significance for me, like a parable. It expresses for me the foundation of my identity as a Pakeha New Zealander, an identity based at the intersection of choice and hospitality. I wonder at my great-grandfather's decision to leave his home, such a young man to leave family and culture, in order to form his own family in a new land. I admire the courage, hard work and determination of my colonial tipuna; Lars died a old man after building up a thriving farm and contributing to NZ’s dairy industry, survived by 11 children (another four died young).

Mostly, though, I reflect on that moment when the muddy exhausted Scandinavians were met on the roadside by Chief Te Awe Awe and a large pile of vegetables. It is consistent with what I know of Maori people, the values of powhiri and manaakitangi (welcome and care for others). It expresses the mana of the man and his people. It also expresses a connection, whakawhanaungatanga, an investment in long-term relationship of reciprocity. Te Awe Awe hoped that these new people, from a land he had only just heard of, would form partnership with his people, in which generosity would be repaid in a cycle of mutual manaakitanga. It raises the question for me personally of whether in my generation we are honouring the challenge of Te Awe Awe, to return the koha to Maori in our time.

The gift that day was of both food and seed, good to eat and an investment in their own new relationship with the whenua (land), enabling them to plant and grow food for themselves. This reminds me of Genesis 1:11 as God calls forth the “plants yielding seed”, beginning the life-sustaining cycles of continuing generations.

This gift required the settlers to unload some of the possessions and leave them behind. This moment speaks to me of the need to choose priorities and to lighten our loads. To truly belong in this land there are things we bring from other places that we must let go. This is a spiritual question asked by Jesus who called people to leave their wealth to follow him (eg. Matthew 19:21), and it applies in a pointed way to those of us who benefit from the injustices of colonisation.

The role of the natural environment in the story intrigues me. Aotearoa did not lay down the welcome mat for Las and his fellow settlers. They trudged their new land knee-deep in mud. Their possessions were washed away by the river. Before they could build homes the winter came, harsh and cold. It was not an easy beginning. It was another six years before Las returned to his land in Whakarongo to plant potatoes and pumpkins. The land of green rolling meadows and stopbanks you drive through north of Palmerston North today once looked very different. Little remains of the forests and swamps that sustained rich biodiversity and food sources for Maori. Te Awe Awe gave of his abundance, but within a generation this was stripped away and his people were battered by war, disease and poverty, despite his choice to side with the British against other iwi. For his sacrifice he won a ceremonial sword and a statue in the Square in the city, but the cost to his people was high.

In our time in ‘Palmy’ I became friends with the current leader of the Rangitane people, himself a Te AweAwe, also a church pastor. My husband and I once hosted him and his wife for a memorable evening over dinner. I shared the story of when our great-grandfathers met that April day, and it meant a lot to both of us, as a sign of God’s provision, the beginnings of Christian fellowship between two very different peoples. My at-home-ness in this land of Aotearoa is based on my great-grandfather’s choice to come here, and Pastor Te AweAwe’s great-grandfather’s choice to welcome him.